Stress, burnout, and their detrimental effects on mental health has produced a toxic stew that collided with the COVID-19 pandemic in ways that altered the basic rhythms of life. Not surprisingly, in the last few years mental health has become a defining issue in many of our lives.

However, directing and learning in a university internship course during the pandemic has illustrated the resilience and grit of students as well as their professors and placement supervisors. This year we were honoured to place a student at the Oakville Museum, who in turn tasked us with research and advising on a prominent Oakville resident: George Brock Chisholm. Over the last year, we have discovered that his ideas are astonishingly relevant to our own time. It is in this spirit that we are eager to share Oakville’s history with a community audience.

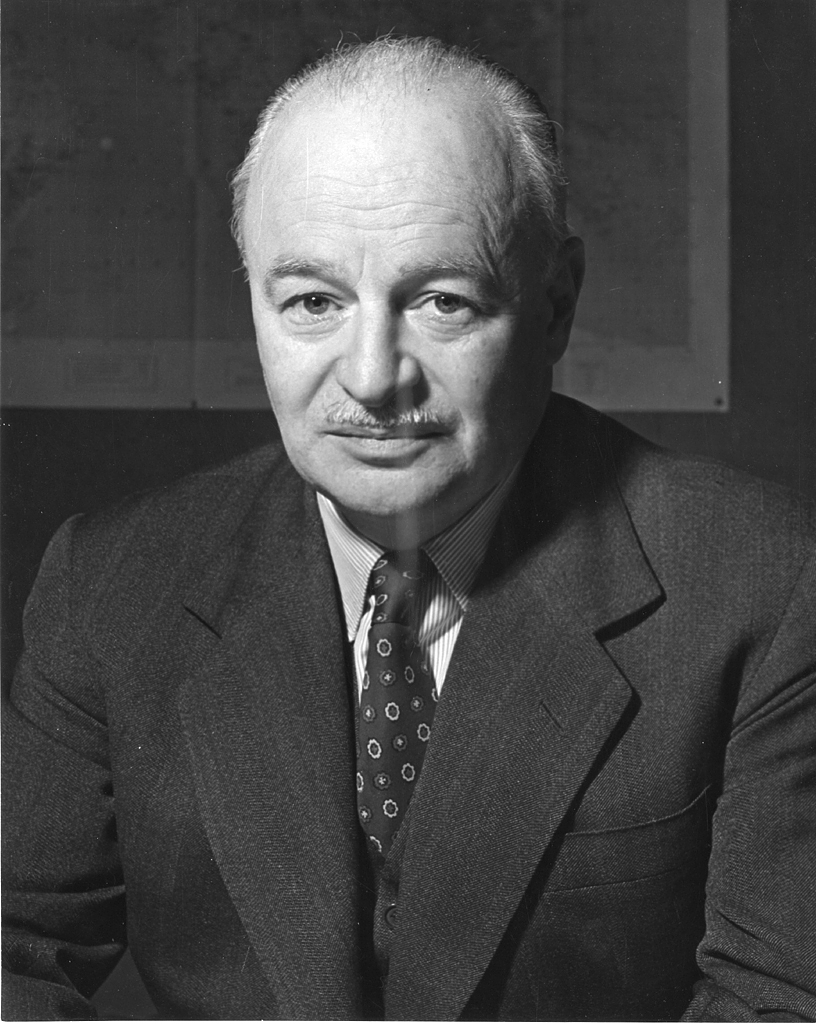

Chisholm came of age in the First and Second World Wars where he saw active fighting and was deeply transformed by the horrors of war. He earned his medical degree from the University of Toronto in 1924 and spent a year of postgraduate study in London in 1925. Chisholm pursued further psychiatry training at Yale’s Institute of Human Relations in 1931, specializing in early childhood development.

He was widely recognized as a brilliant scholar. After World War Two, he became the Director General of the World Health Organization (WHO). He, along with other functionaries, drafted the WHO’s constitution that prioritized both mental health and individualized physical well-being.

We might assume a separation between mind and body. But for Chisholm, this distinction misses the mark. To him, mental health and the health of entire peoples and nations were the same. If, after all, how we think is intimately related to how we feel then it’s a small leap to argue that the fate of nations and world peace is intimately connected to our collective health. Indeed, this is a lesson that COVID had to teach us again and gain.

“Emotional health of individual citizens affects external relations,” declared Chisholm.

On February 26, 1946, during the William Alanson White Memorial Lecture in New York, Chisholm declared, “emotional health of individual citizens affects external relations.” This was a radical claim for the time. The looming Cold War—and, of course, world nuclear annihilation—produced its own set of anxieties over the future that Chisholm believed could be overcome through a combination of strictly applied reason and education rooted in an incessant questioning of “established truths.” This approach to learning would ultimately lead people away from flawed patterns of thinking and would produce clearer minds, healthier bodies, and a more peaceful world.

What Chisholm wanted to do was eliminate human pathologies that led to war and create universally applicable policies to bring about a peaceful planet. “We are the kind of people who fight wars every fifteen of twenty years. Why?” The overarching answer centred on human bias and what we might call prejudiced patterns of thinking.

Circling back to his education at the University of Toronto and Yale, he sought answers in early childhood education. According to him, national prejudice, attachment to clan and ethnicity, or religious intolerance were essentially baked into contemporary institutions. These biases produced a collective sickness of emotional rather than critical thinkers who went on to create the horrors of authoritarianism and the threat of nuclear war. His program for reform centred on teaching young people to grow “emotionally beyond national boundaries” to become “world citizens.” These world citizens would possess a healthy “emotional relationship” with people of all walks of life and have “loyalty to the human race as such” (our emphasis).

Chisholm’s idea of “world citizenship” as a way to refashion the world around mutual respect and acceptance of difference inspires thought and, in our own day and age, are very much worth considering. In an era where we reckon with historical injustice and renewed European conflict—the war in Ukraine being the largest since Chisholm’s time and Vladimir Putin’s suspension of Russia’s participation in the new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START)—ushers in a new age of nuclear armament, it is wise to consult those that have faced similar problems and sought solutions in the highest aspirations of humanity. The post-pandemic world need not be one characterized by isolation and conflict. If we study the past and the ideas that wise people articulated in the time of fundamental global crisis, we can find healthy and intelligent solutions for our collective future.